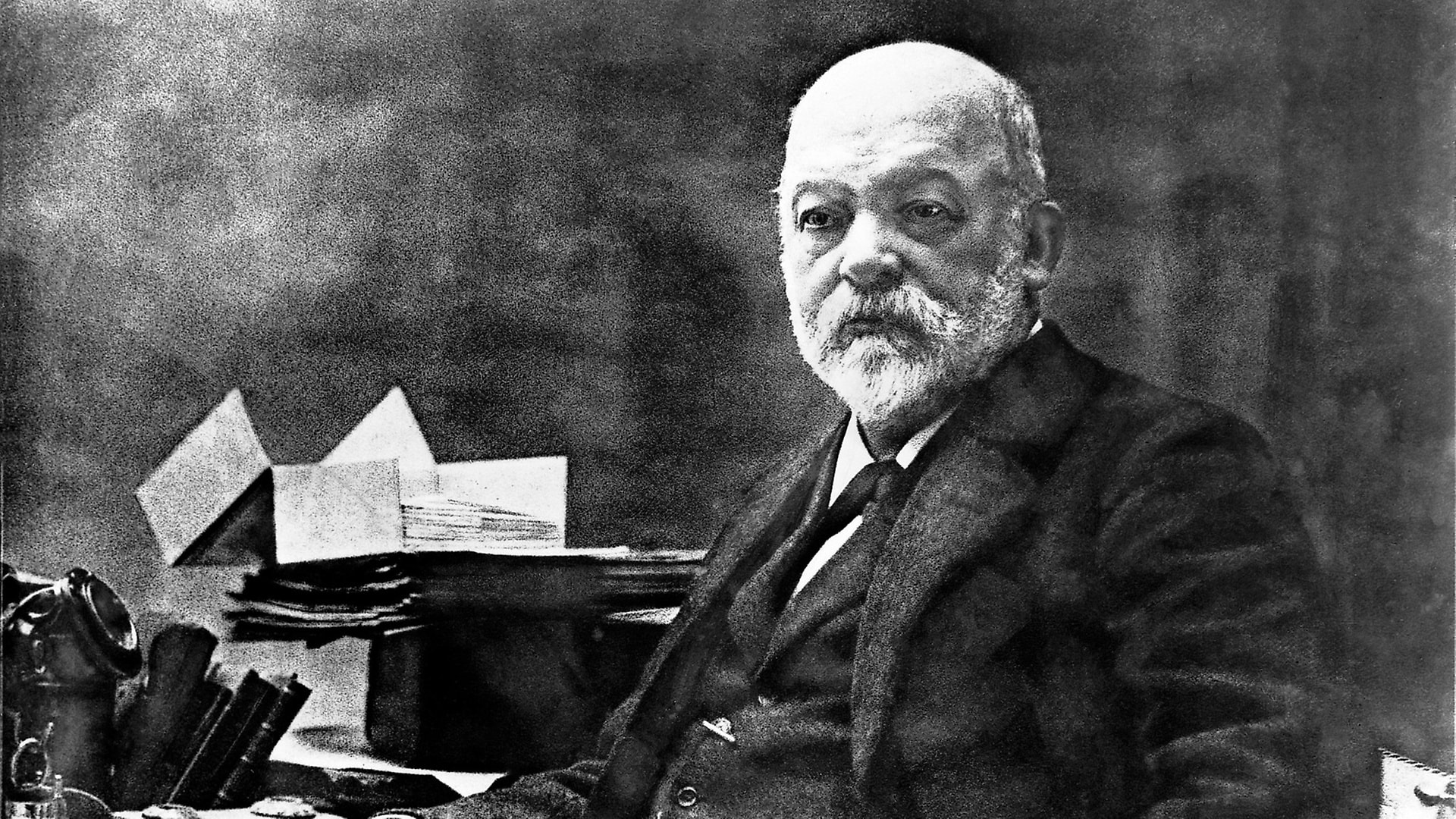

Early on, both Gottlieb Daimler and Carl Benz endeavoured to market their inventions internationally.

Unlike Carl Benz, who initially only had an agent representing him in France, Gottlieb Daimler was able to make use of several foreign contacts.

He succeeded in concluding licence agreements especially in France and Britain.

At the 1876 World Exposition in Philadelphia, Wilhelm Maybachhad made the acquaintance of William Steinway and introduced him to Gottlieb Daimler at the end of the 1880s. Following his visit to Cannstatt, Steinway secured himself the contractual right of exclusive representation for the entire Daimler product range in the USA and Canada.

Carl Benz did not manage to forge closer foreign contacts until the end of the 19th century. In addition to Britain, he celebrated surprising successes in the USA and South Africa.

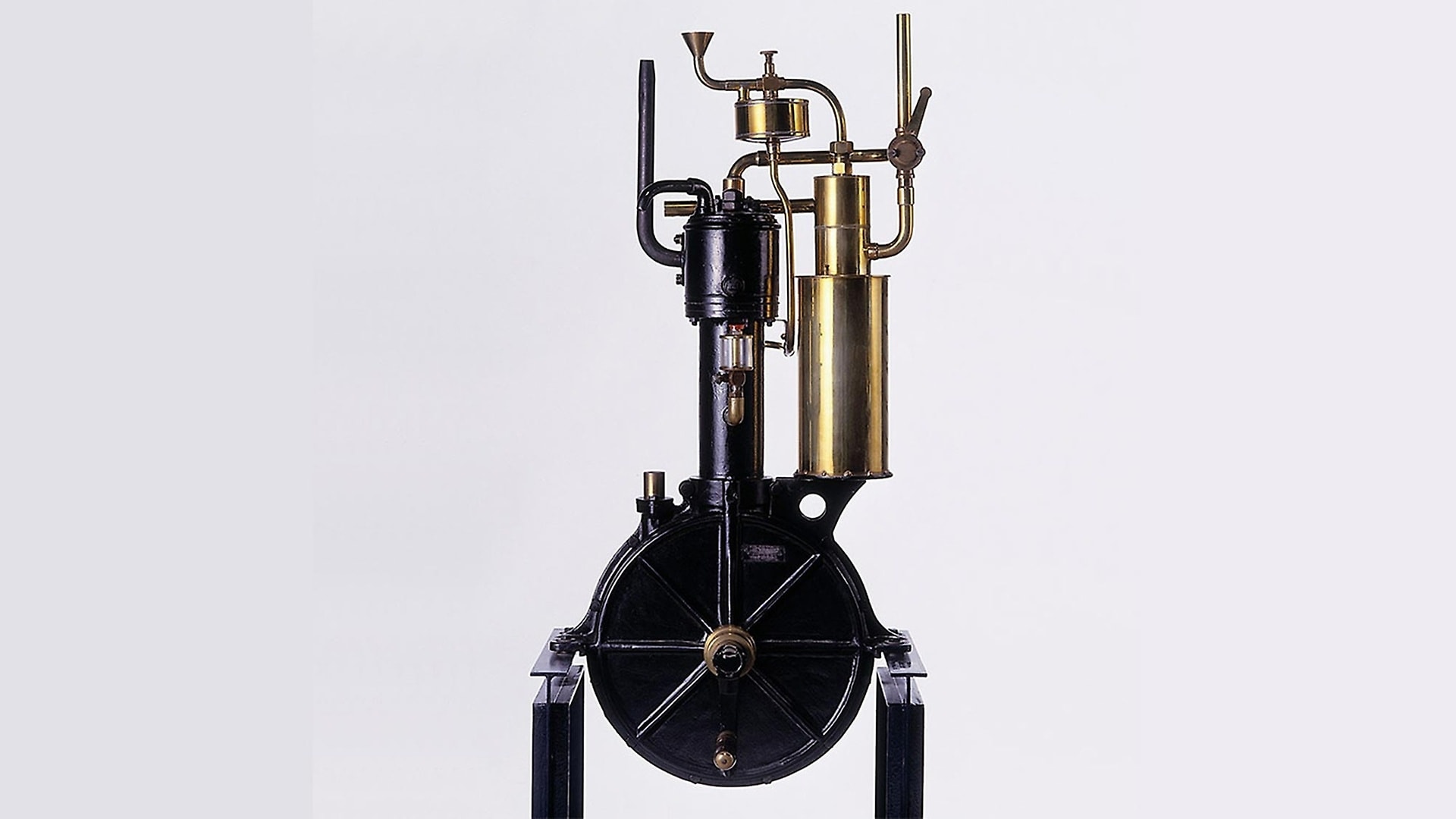

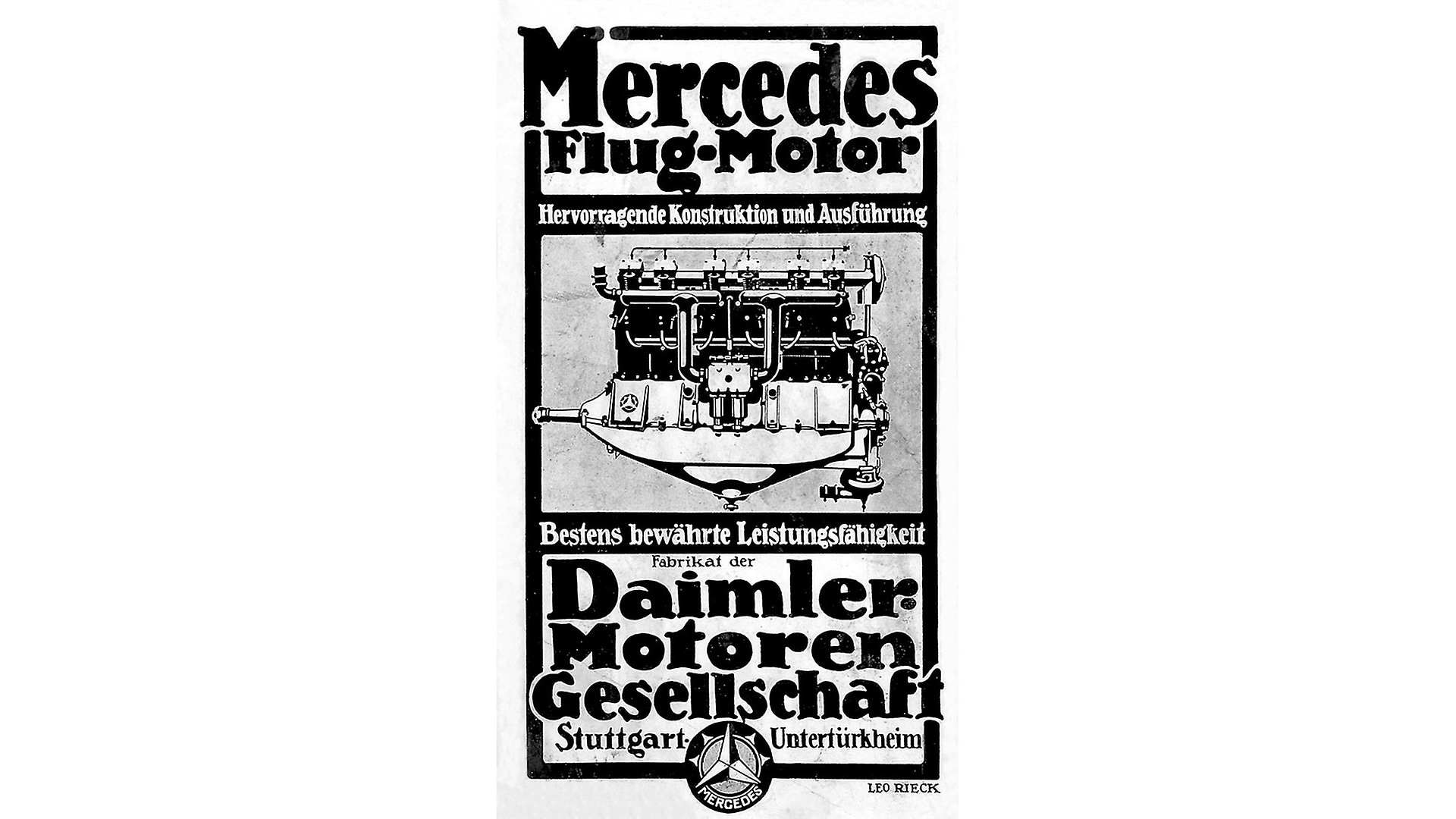

Apart from their efforts to gain a foothold in foreign markets, both pioneers pressed ahead with the continuous technical improvement of their products. For instance, Wilhelm Maybach, working as an engineer at DMG, developed the spray-nozzle carburettor, a milestone in the success story of the automobile.

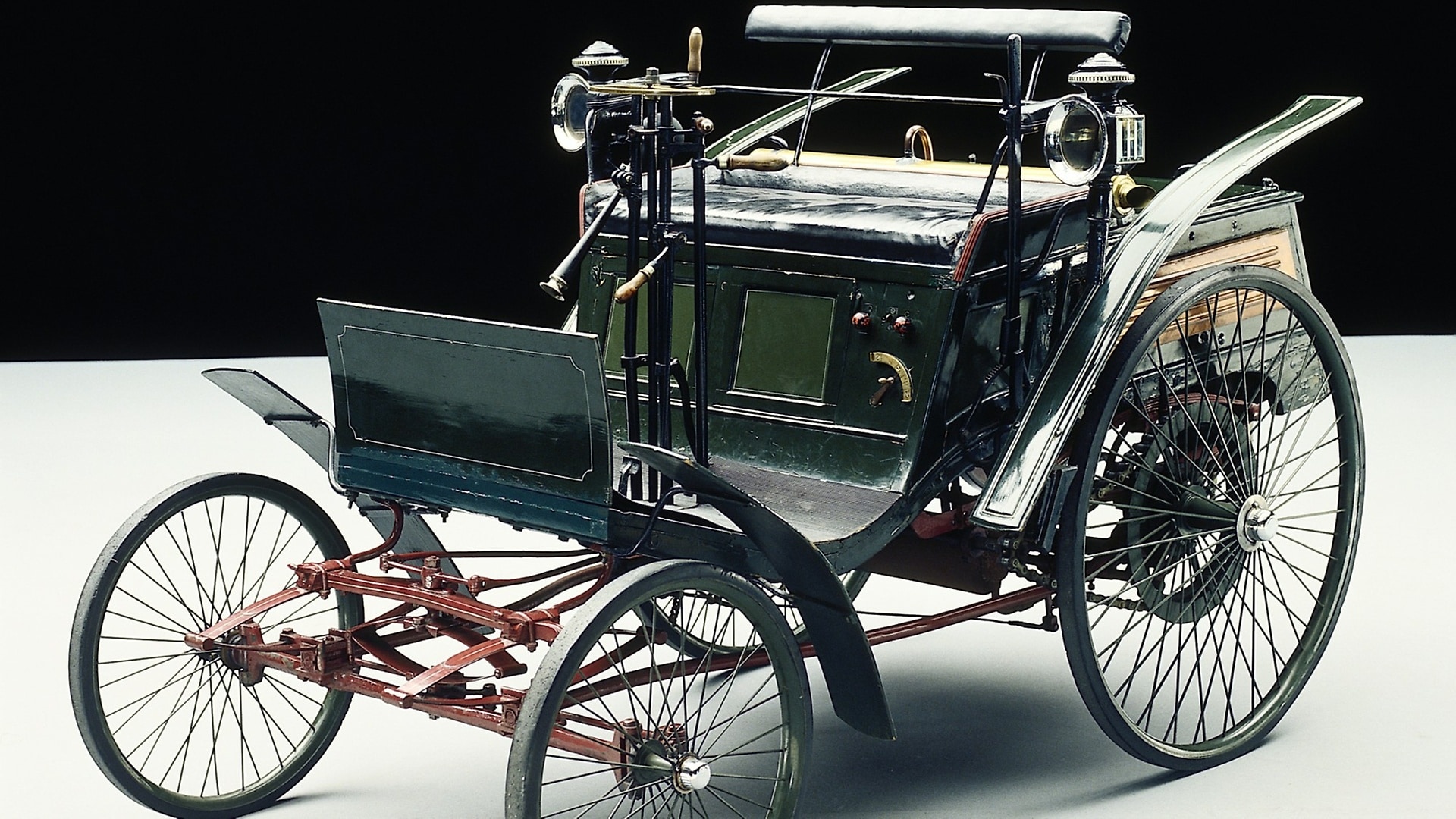

This innovation represented a major breakthrough in engine design and the principle behind it is still applied to this day. The first major long-distance tours in France and Britain demonstrated the superiority of the petrol engine over its steam counterpart. The outstanding performance of the Daimler engines marked the technical breakthrough for the automobile.

Carl Benz achieved another crucial technical breakthrough in 1893 by inventing double-pivot steering, which solved the problem of steering four-wheeled vehicles.

,xPosition=0,yPosition=0.5)

,xPosition=0.5,yPosition=0)

,xPosition=0.5,yPosition=0)

,xPosition=0.5,yPosition=0)