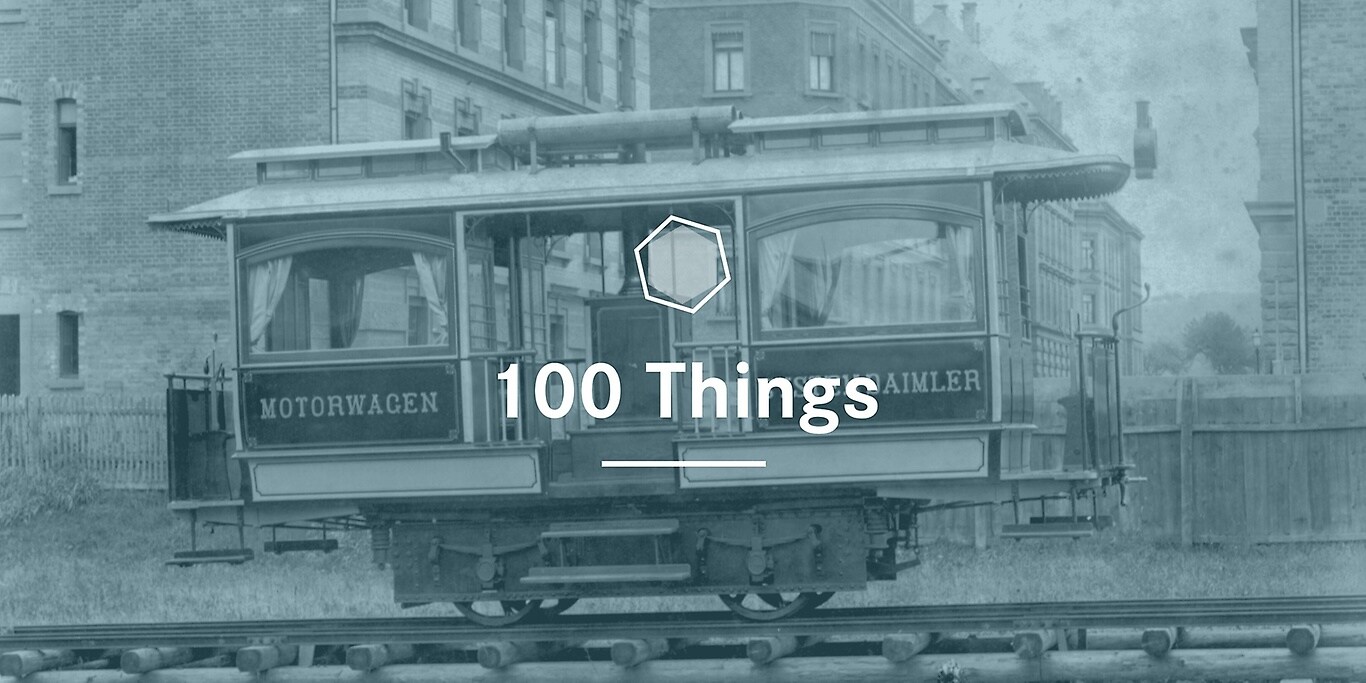

Admittedly, the Daimler Motor-Draisine’s technical data — 1.1 horsepower, four seats, and a top speed of 20 kilometers per hour — didn’t appear to be serious competition for the railroad. But was it really so hopeless? No, because the world’s first rail vehicle with a gasoline engine would beat any other in the “year of manufacture” category: A draisine and a railcar from Daimler had already been tested on the route between Esslingen am Neckar and Kirchheim/Teck in 1887.

But that was just the beginning for motorized rail mobility: In the same year, Daimler put a narrow-gauge streetcar into operation at the Cannstatter Wasen fairground. It caused a minor sensation, because in the late 19th century streetcars were generally pulled by horses or mules. As is the case with many innovations, Daimler’s replacement of the draft animals with tractor units was viewed skeptically by many of his contemporaries.